Welcome to Coastal NYC!

AS-L Project

Part 1

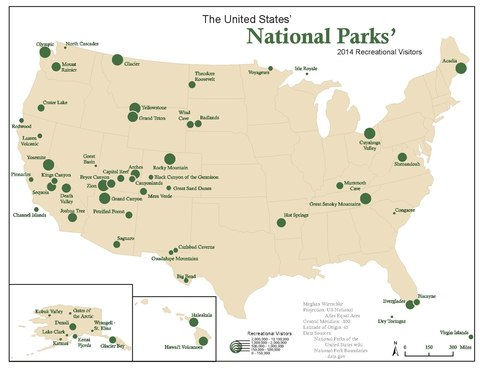

In the United States, environmentalism stemmed from the conservation and preservation movements of the late 1800s and early 1900s. While rapid urbanization and industrialization was advancing American society, it was depleting the nation of its natural resources in order to support a growing population. Therefore, conservationists began to approach the issue in a way that would limit the resources that would be spent in order to ensure the young nation’s success (Silveira 2). President Theodore Roosevelt was one of the early proponents of conservatism, and his preservationist motives made him the father of the National Park Service.

However, this does not take away from how environmentalism is a movement that began out of privilege. Being able to afford leisure time in nature is an amenity that not all can enjoy. Even further, many National Parks were often built on indigenous land, therefore displacing the tribes that called those places home (Schlangen). During the 1960s, legal battles with the courts for federal environmental protections “helped to make environmentalism intensely a movement of lawyers and experts, funded by middle-class mass-membership groups and wealthy donors, and not driven by large-scale mobilization or engagement,” (Britton-Purdy). It was not until the first Earth Day, in April of 1970, that the masses organized for an environmentalist cause.

In our contemporary society, there is a growing emphasis on environmental justice, and not strictly conservation or preservation. Environmental justice can take many forms, but one of its most prominent sectors is the issue of environmental racism. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the effects of environmental racism have been exacerbated to the highest degree. Those that are predisposed to sickness from the atrocities that corporations and government have caused have suffered the most during the pandemic. It is the hopes of the environmental justice movement to shed light upon these inequalities and rebuild the systems that allow these crimes against humanity to happen.

Part 2

In the “Snow Spotter” Zooniverse project, hydrologists from the University of Washington engage with the community through citizen-science to classify the snow-coverage on treetops in various locations. On their site, you can choose to classify images from Niwot Ridge, Colorado, or Sodankyla, Finland. Depending on when the site is being accessed, you have the opportunity to choose from other locations, as well, but as the project progresses, the selection of images changes. For example, past locations that have since been completed include Olympic National Park in Washington and Sequoia National Park in California.

The hydrologists have set up cameras at various locations in these parks, and they automatically take images every thirty minutes. These images are then sent to Zooniverse for the community to ascertain whether or not there is sufficient snow coverage on the trees. Alternatively, for the Niwot Ridge location, volunteers can report back how much snow is present, as well.

The objective of this project is to explore how much water can be stored in these snow caps that cover the trees. According to the Zooniverse page, “Forests can intercept up to 60% of the total annual snowfall, and 25-45% of this snow can be sublimated back into the atmosphere.” Therefore, each classification helps the scientists explore the relationship between fresh water storage and the presence of snow caps in the forests.

Since the cameras that the scientists installed take pictures every thirty minutes, I understood that these cameras collect a lot of images over time. In my opinion, that makes Zooniverse the perfect platform for collaborative science. Without people like me to sort through the data, the researchers would undeniably be overwhelmed with work that would take an incredible amount of time to sift through. The numbers do not lie: the research team claims that almost 7,000 people have made 150,000 classifications!

I have never done online citizen science before, so using the Zooniverse platform was a very personally enriching experience. I particularly enjoyed exploring the site and sampling various projects to see which one peaked my interest. What makes the Zooniverse site so great to interact with is that each project has its own unique page with the appropriate directions and resources. However, in the beginning of my academic service learning, I had to overcome the learning curve of making classifications and understanding the technicalities of my account. With regards to making improvements, I think I would work on making the site more user friendly and easy to navigate. In the future, I will definitely look to sites like this to find more creative ways to stay engaged with environmentalism and science in general.

Works Cited

Britton-Purdy, Jedediah. “Environmentalism Was Once a Social-Justice Movement.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Dec. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/12/how-the-environmental-movement-can-recover-its-soul/509831/.

Schlangen, Kaija. “Environmentalism vs. Environmental Justice.” D.umn.edu, University of Minnesota Duluth, 29 Sept. 2020, www.d.umn.edu/sustainability/news/environmentalism.

Silveira, Stacy J. “THE AMERICAN ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENT: SURVIVING THROUGH DIVERSITY.” Bc.edu, Boston College, www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/schools/law/lawreviews/journals/bcealr/28_2-3/07_TXT.tm.

http://foundations.uwgb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/The_silent_highwayman.jpg

https://www.pophistorydig.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Richard-Ellers-hand-320.jpg

https://news.climate.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/earth-day-1970-768x513.jpg

https://www.clf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Detail-ClimateJustice-shutterstock.jpg

http://www.protrails.com/protrails/trails/326.jpg